Prototyping a Custom GameBoy Cart

01 Feb 2026 ∞

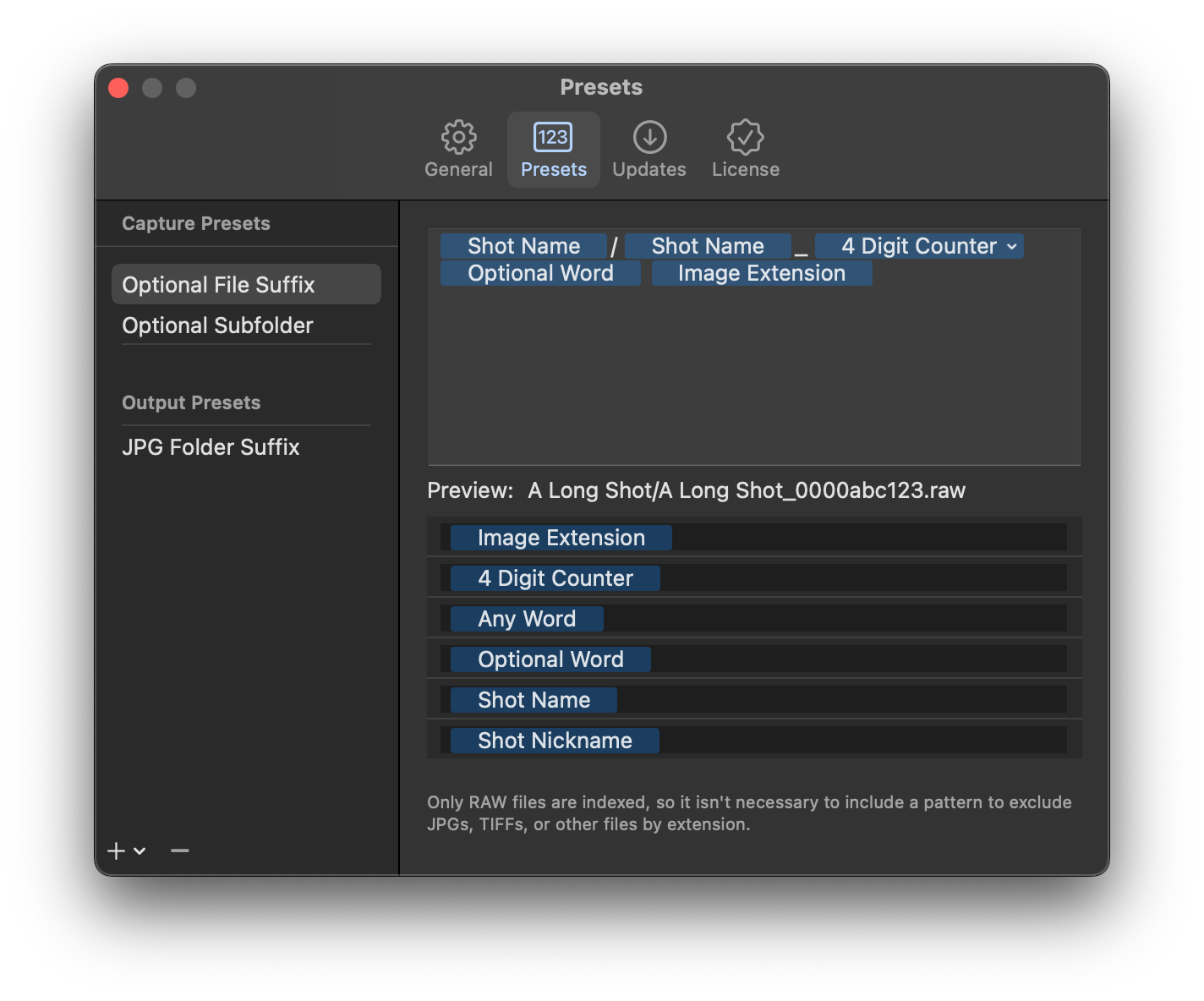

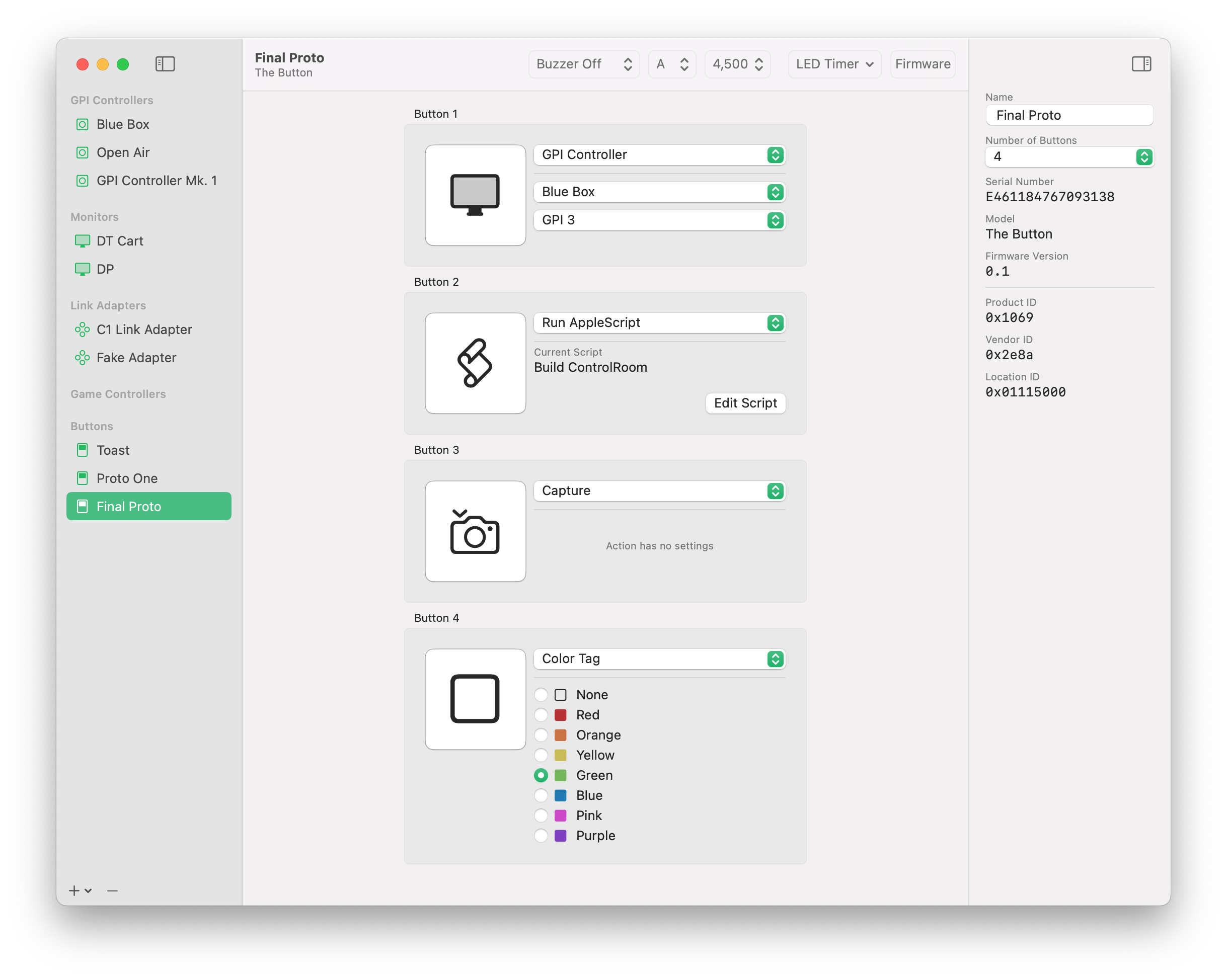

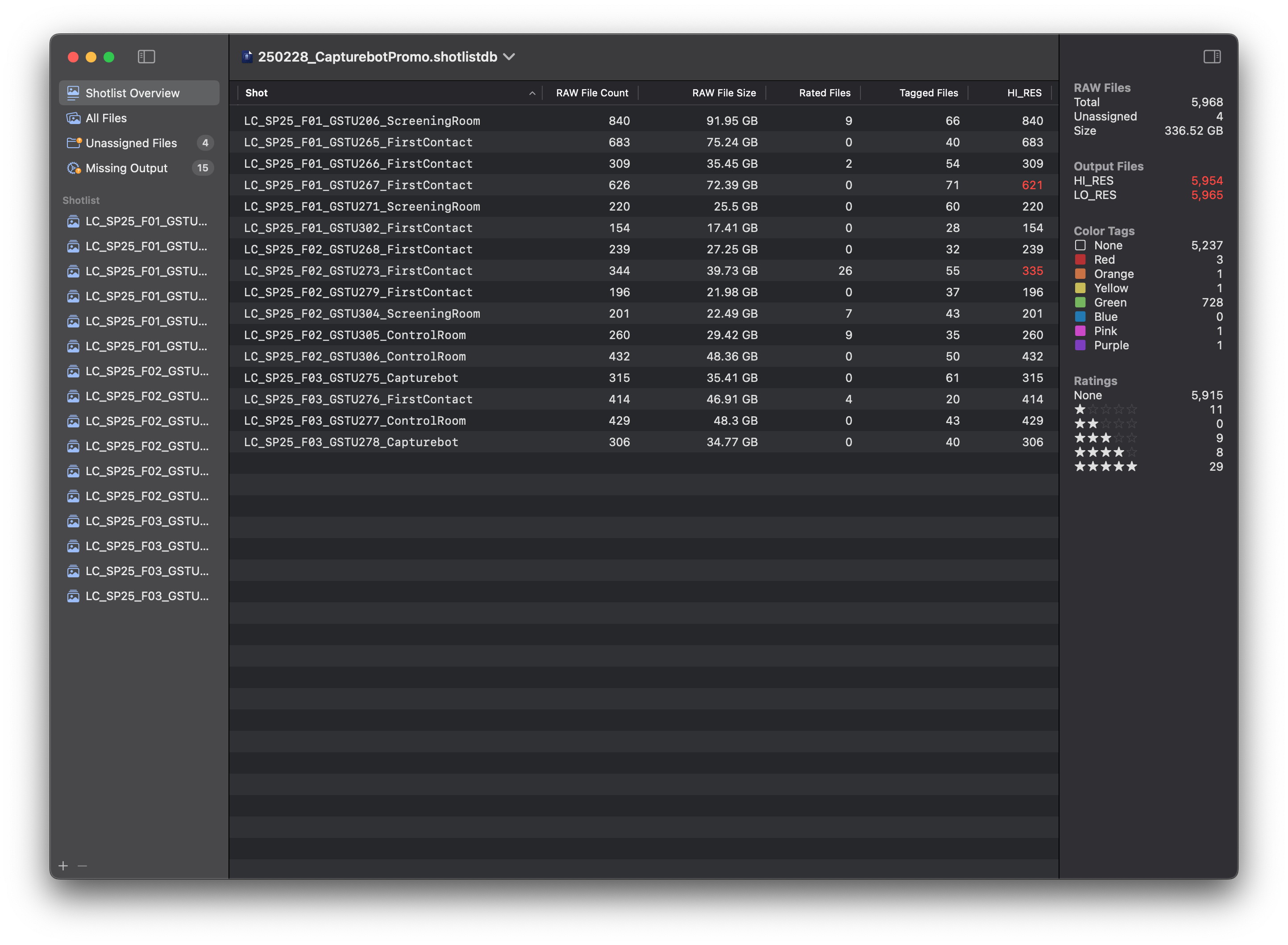

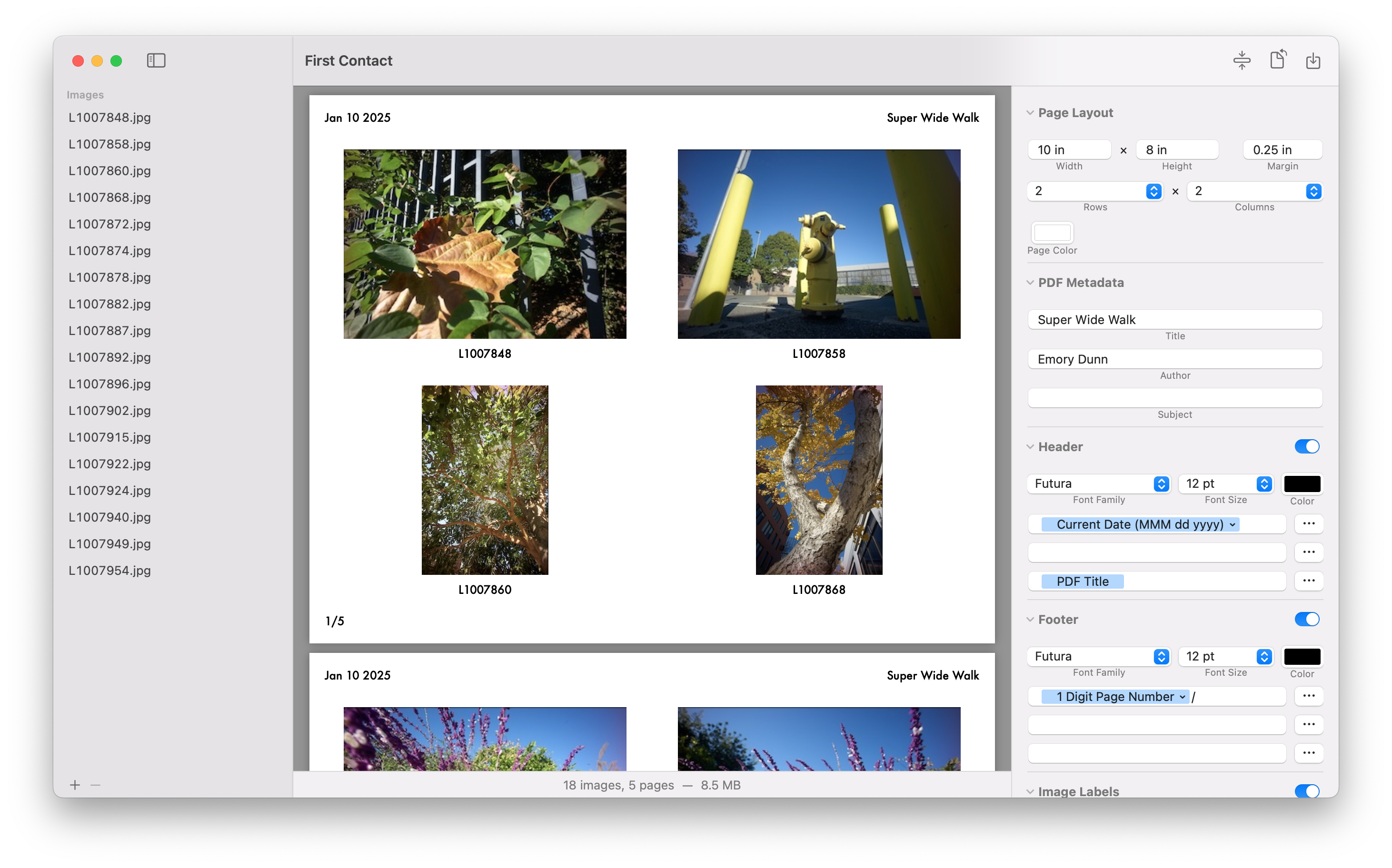

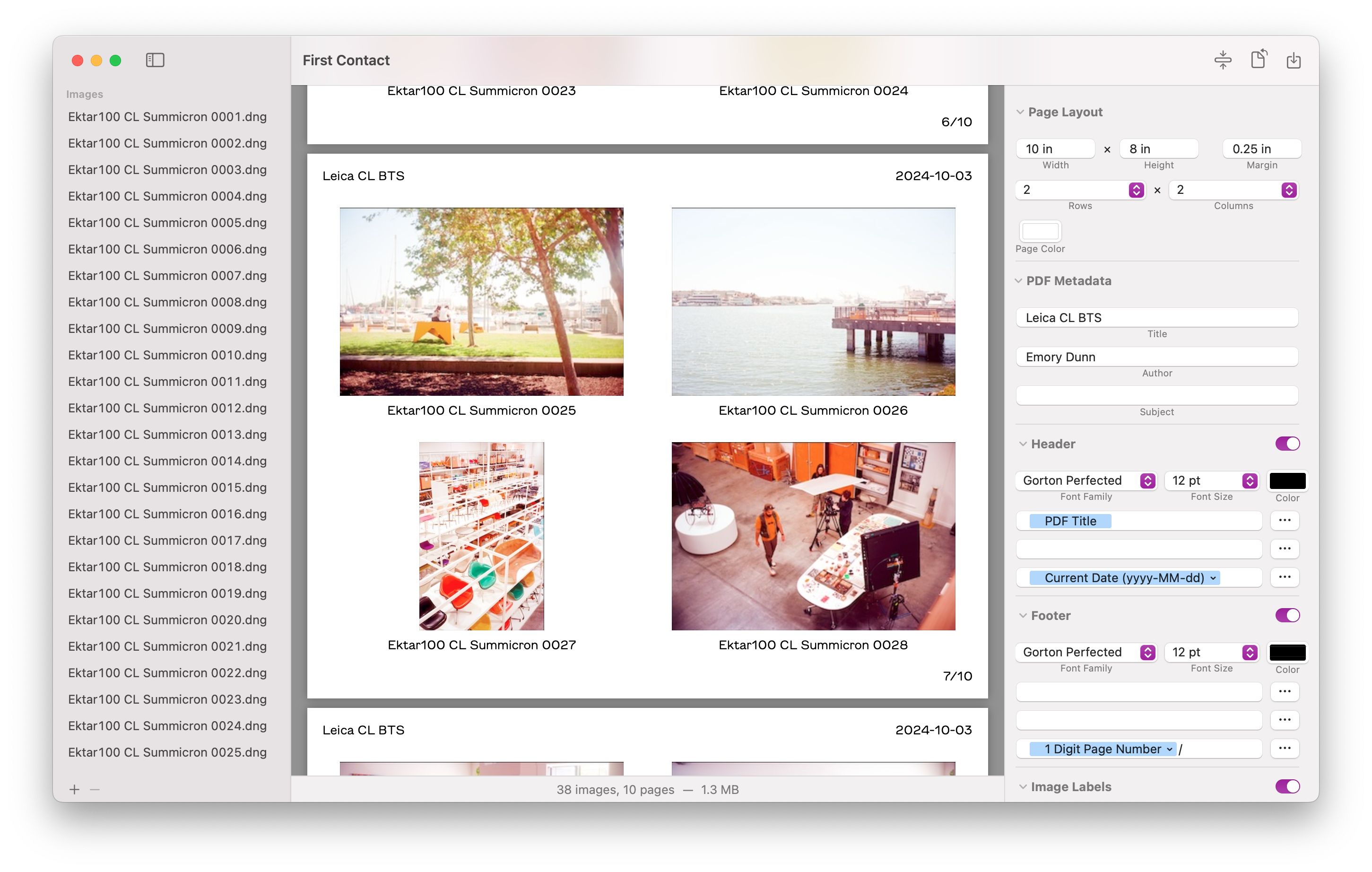

A couple years ago I built a GameBoy app and hardware accessory for controlling Capture One. It was a great project, and I learned about GameBoy programming for the first time, did a deeper dive on embedded Swift, and explored wireless communication on a lower level. The result worked surprisingly well, allowing someone to navigate images and set color tags & star ratings.

The project wasn't the most user-friendly, requiring something like an Analogue Pocket to load the ROM and the hardware used the link cable, which meant a wire to manage. I knew I wanted to take it a level further: a custom all-in-one GameBoy cartridge that housed all of the components.

I figured it ought to be possible, after all modern microcontrollers are fast, why not just wire up the edge connector pins to GPIO and call it a day? It didn't take long to realize that, perhaps, wasn't the best course of action. It would make more sense to let the microcontroller handle coordination and use an EEPROM for the GameBoy side of things.

After thinking about some of the basics I came up with a set of requirements for my cart:

- Entirely self-contained

- Wireless communication to a computer

- GameBoy to RP2040 communication via RAM

- Flashable EEPROM from the RP2040

The EEPROM

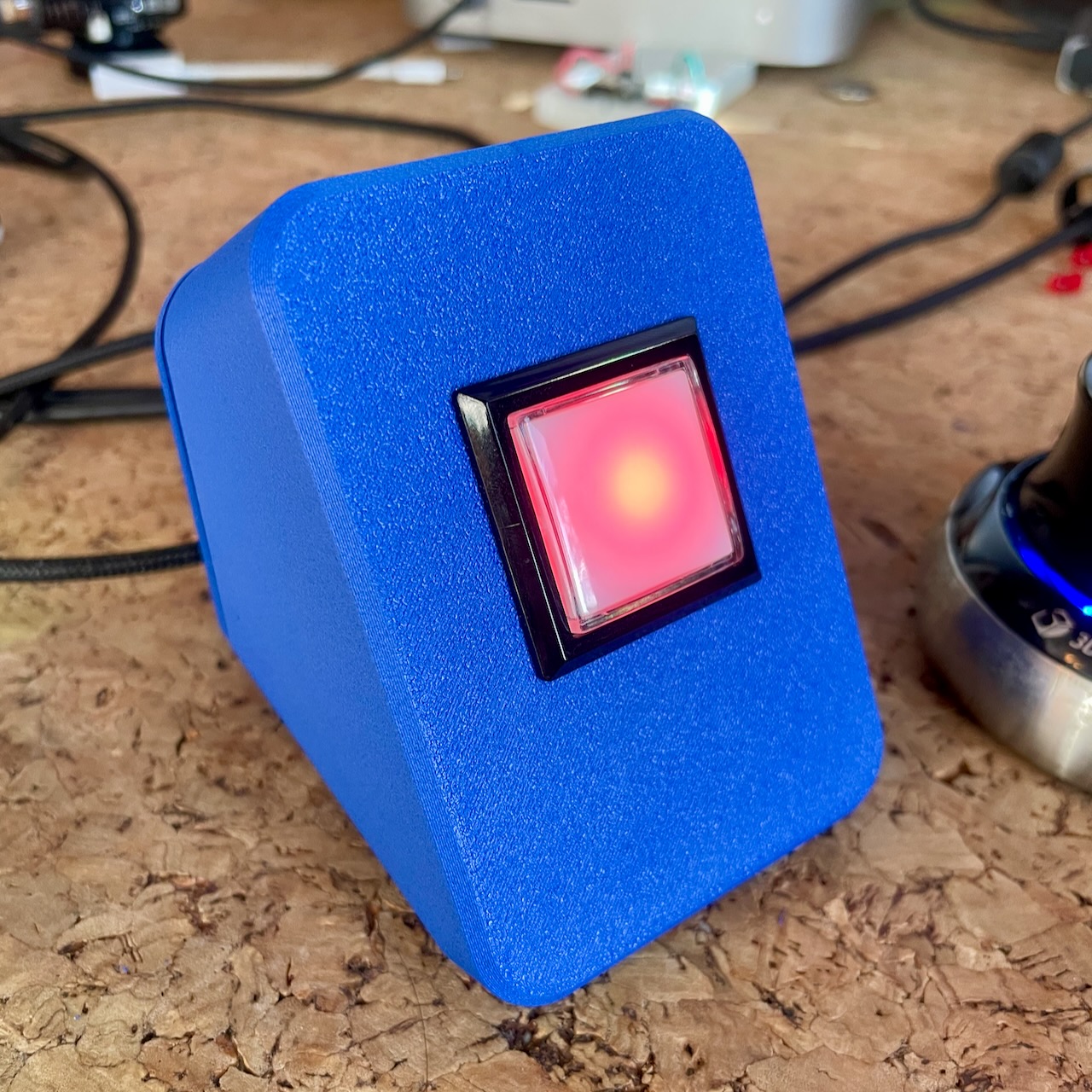

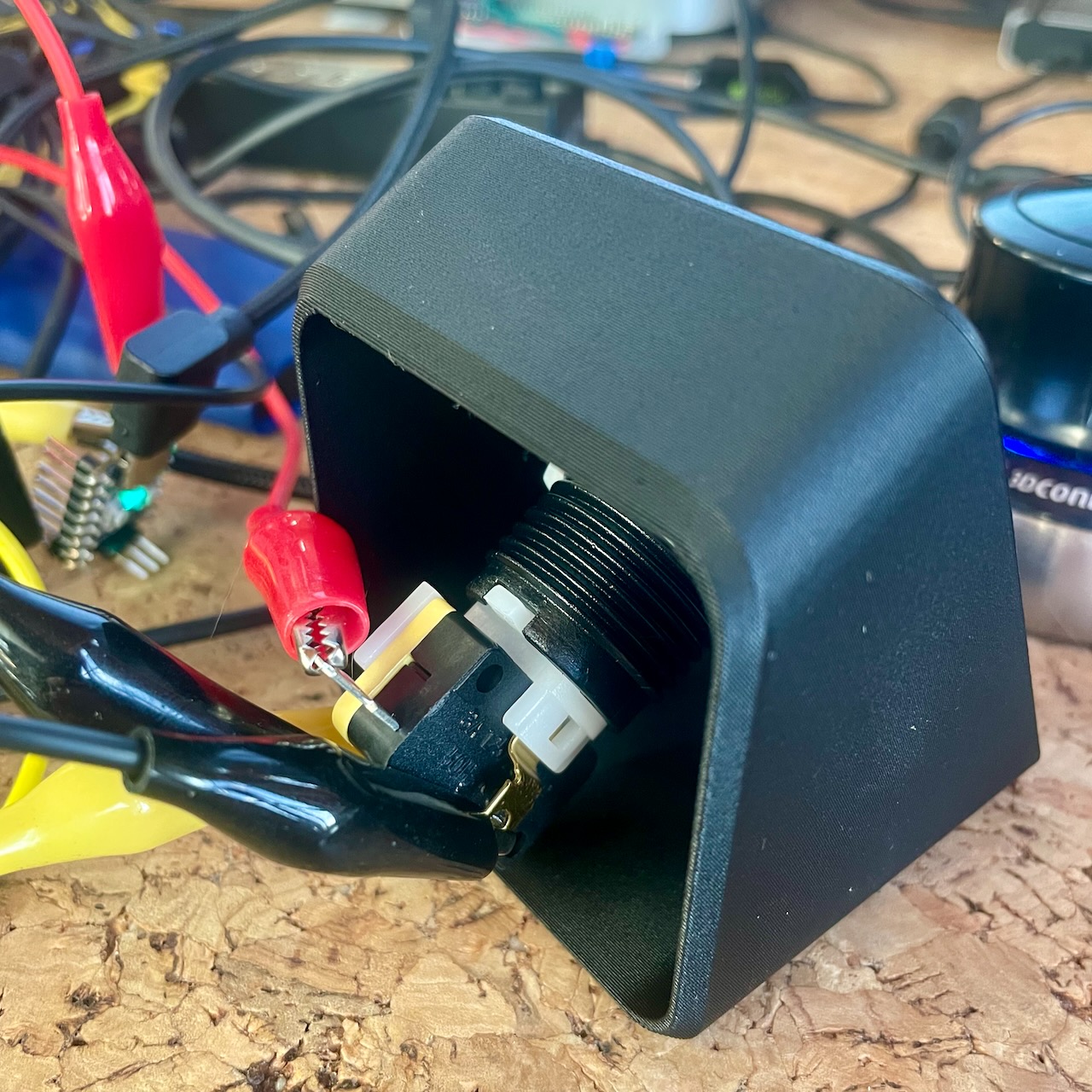

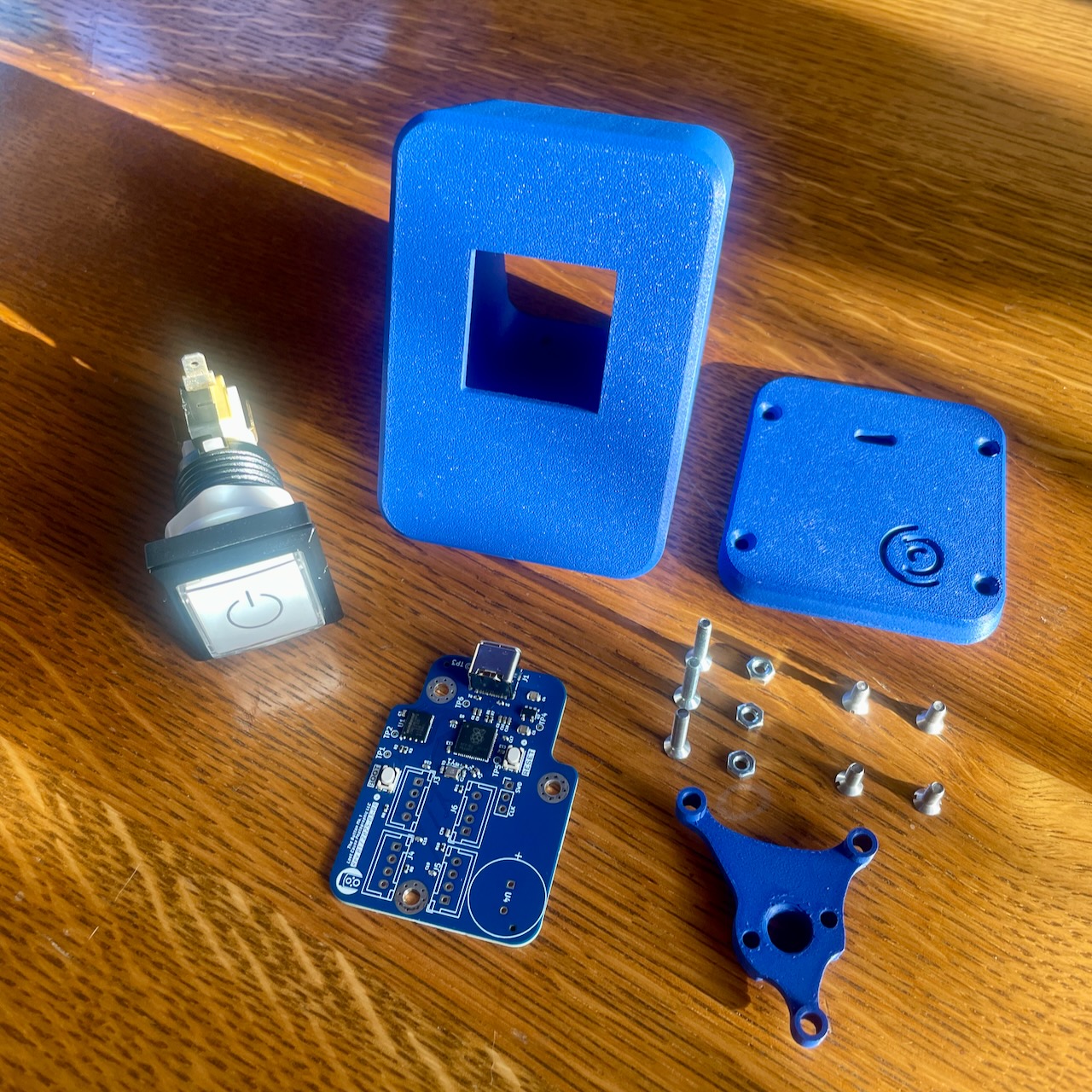

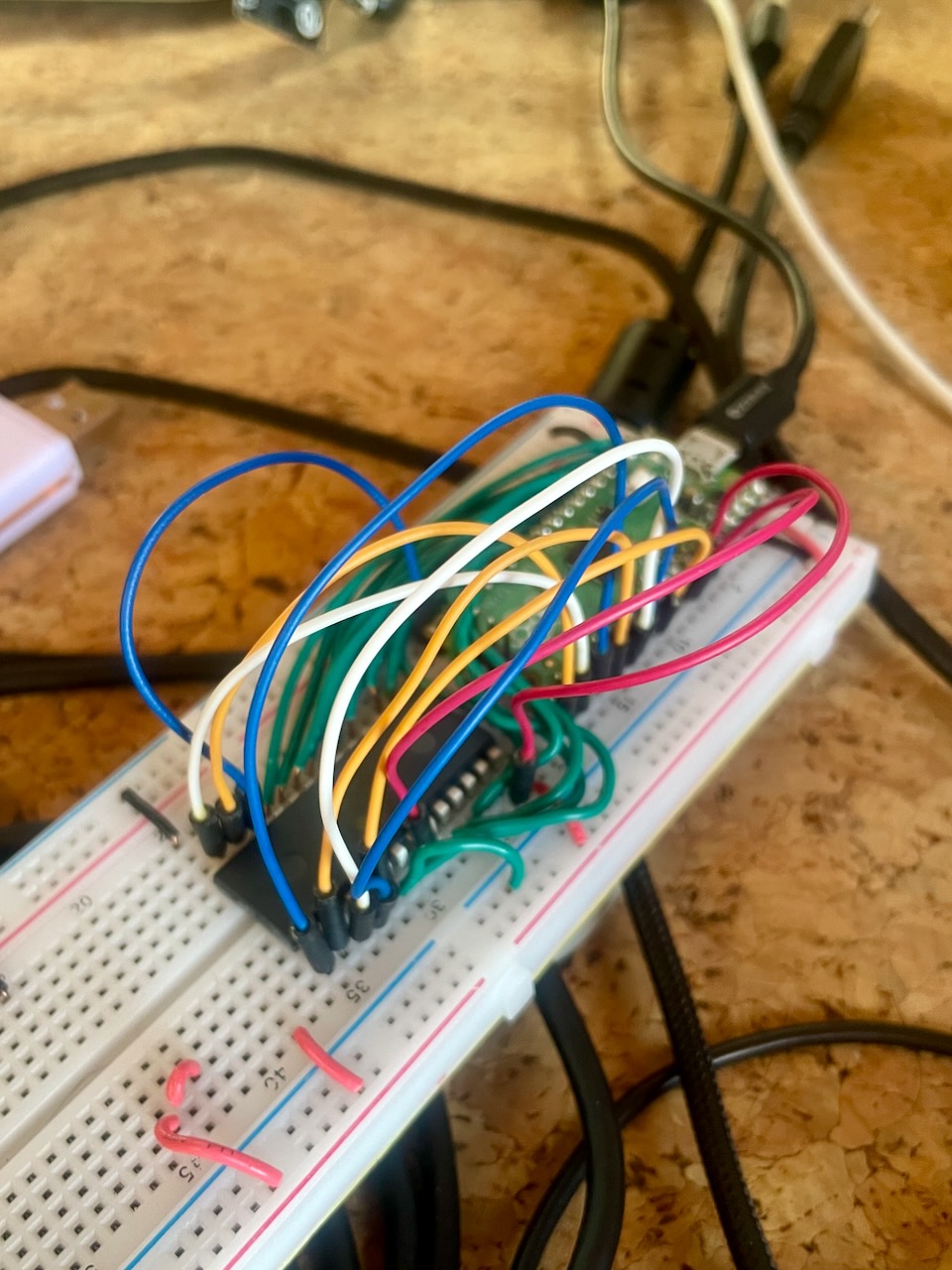

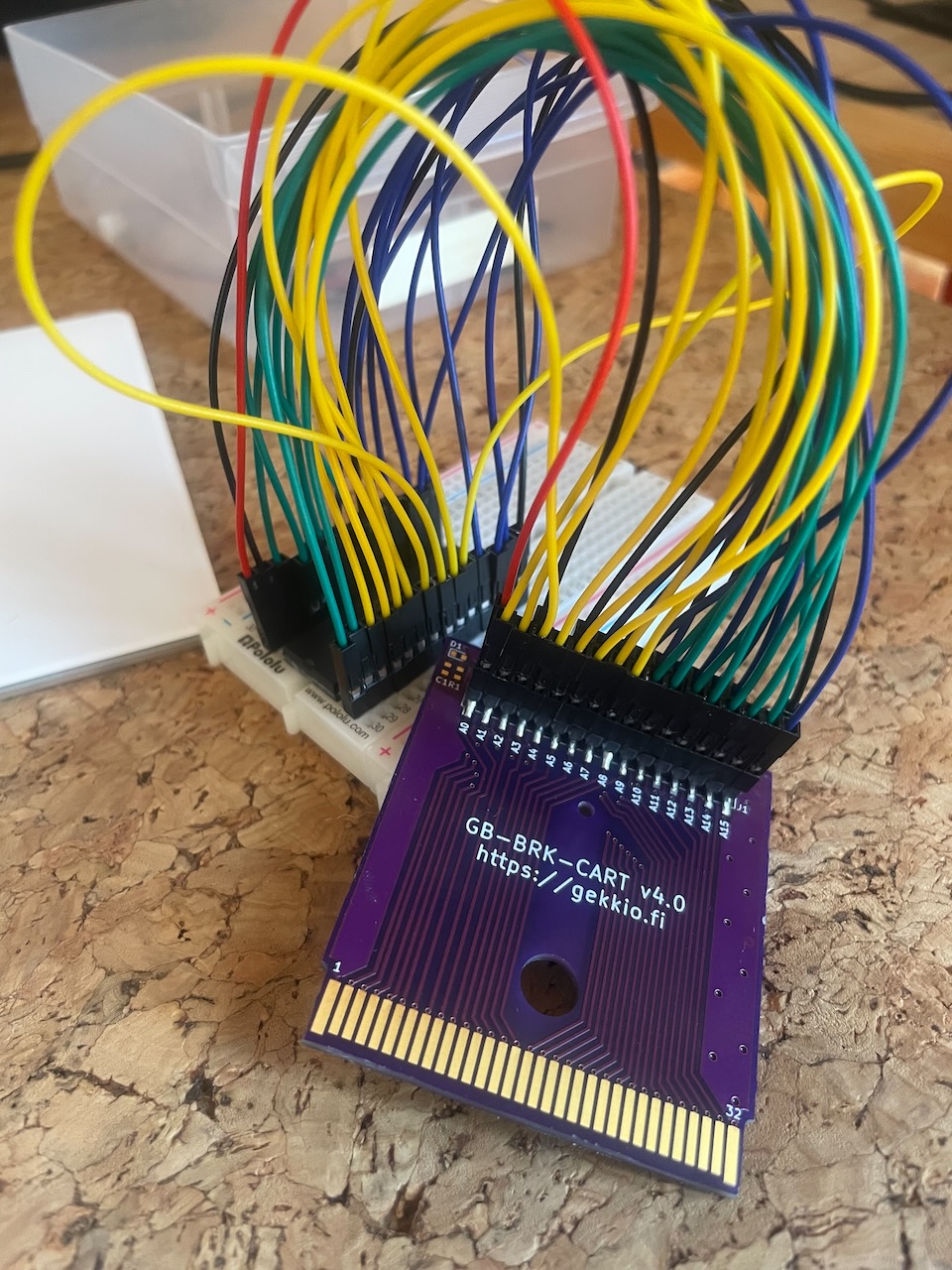

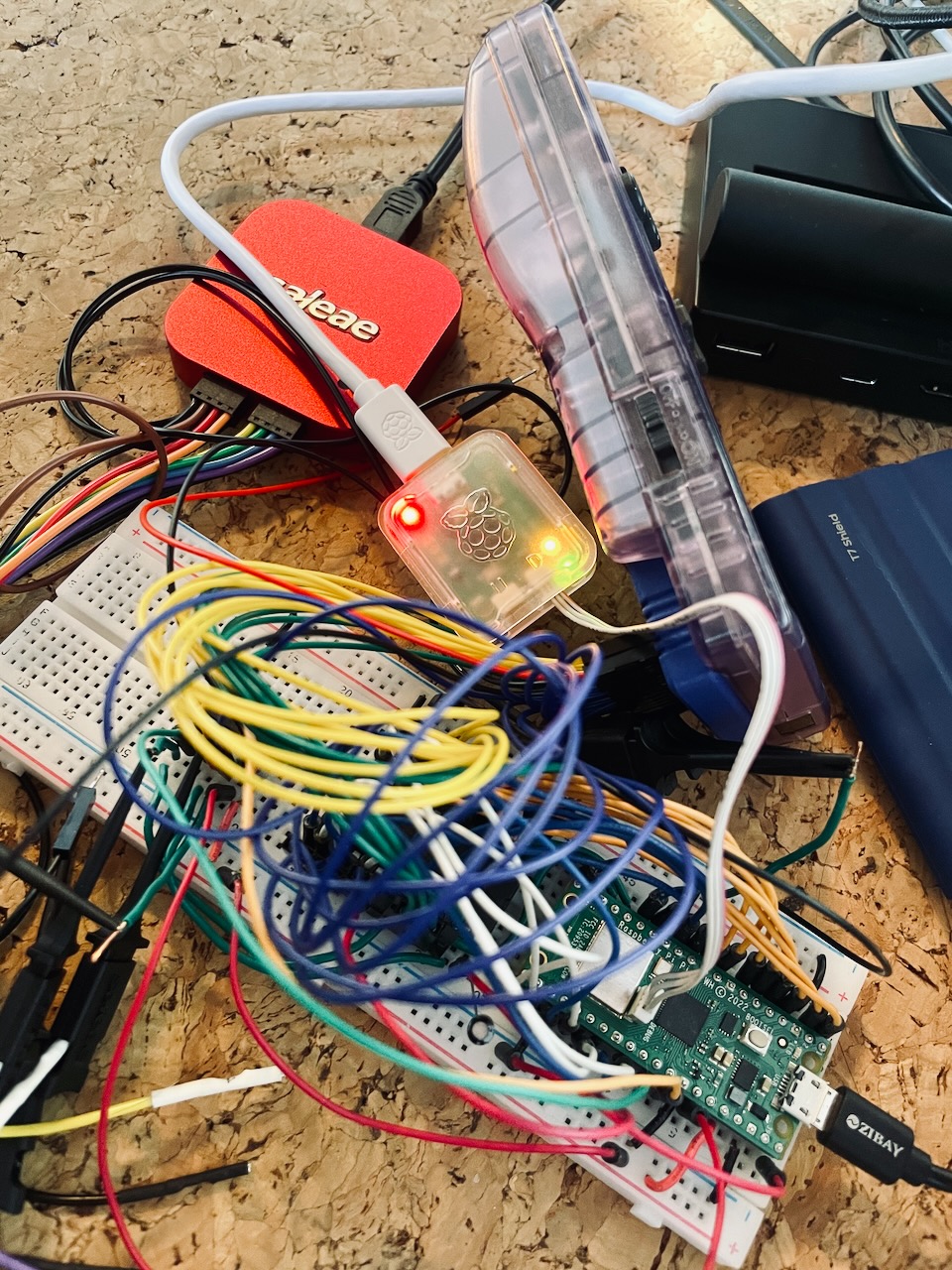

I didn't have a dedicated EEPROM flasher, so I started by building one with a Pico as that was one of the design goals anyway. The EEPROM is fairly simple: you give it an address, ask to read or write, and then it either puts some data on the bus or you do. The timing for reading or writing are generous, it could even be done by hand. There are 16 address lines, eight data lines, plus control logic, all which need to be connected between the EEPROM, the Pico, and the cart header, all just a matter of connecting a bunch of jumper wires.

There was a little bit of logic needed around reading and writing. A normal game is read-only, and the EEPROM is hard wired that way. In order for the Pico to write to the EEPROM we can't do that, the pin needs to be controllable. Unfortunately the write enable pin isn't only used when writing to the EEPROM, it's used when writing anything to the bus. As a result if we simply connected the pin we'd end up rewriting our game code with garbage.

To solve this I pulled some logic gates out of the components drawer and got to work. While the GameBoy has 16 address lines, the EEPROM itself only has 15. In fact, that high bit is only low when the GameBoy wants to access the ROM, all other addresses on the bus leave it high, so run everything through an OR gate and we should be all set1.

Getting the EEPROM to flash successfully took a fair amount of work, lots of wiring issues and bugs in my code. Then finally it worked. Watching my own code boot on my childhood GameBoy was nothing short of amazing, and still hasn't gotten old2.

The Bus

When I built the prototype I used the link port for communication, as that was the only way for the GameBoy to send data to the outside world. The link port communicates via SPI, shifting one bit at a time, which was fine, but could be better for our use case. The GameBoy supports external RAM, usually used for save states, but why not have the RP2040 act as write-only memory?

Modifying the code was easy, instead of sending data via the link port all it takes is writing data to specific addresses. I chose the first few bytes of RAM:

uint8_t* RP_KEY = (uint8_t*) 0xA001;

uint8_t* RP_VALUE = (uint8_t*) 0xA002;

This way simply writing a value to either property causes the GameBoy to write the data to the bus, including pulling the write enable low. To test this I loaded the ROM up in a GameBoy emulator and debugger called bgb. Watching the memory inspector confirmed that our bytes were indeed being written to RAM as expected when I pressed a button.

As for wiring, everything was already done! The Pico was already on the bus, so it just had to wait for its stop3. This is where I ran into some issues. My initial approach was to set an interrupt on the write enable pin and then check if an address was either of our pointers and then pull the data. This did not work, there was just too much happening on the bus. Even running the interrupt on the second core by the time the interrupt was serviced the GameBoy was onto the next thing.

I ended up having to put the second core in a fast loop just checking the write enable and address lines, and even then had to have the game write the same data to RAM multiple times to ensure the Pico would catch one of them. There are some other projects which suggest this could be handled by PIO, though adding address decoding with discrete logic to filter out anything other than writes to the external RAM is another option.

Wireless

The final step in all of this was adding wireless communication so the GameBoy wouldn't need to be tethered to a computer. I'd been prototyping with a normal Pico, so I swapped it out for a Pico-W and got to work. The client app ran a basic socket server to which the Pico would connect and send the full command (both the key and value). Getting the Pico connected to Wi-Fi with stored credentials turned out to be the hardest part.

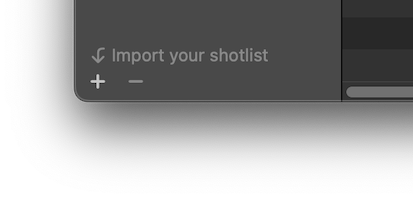

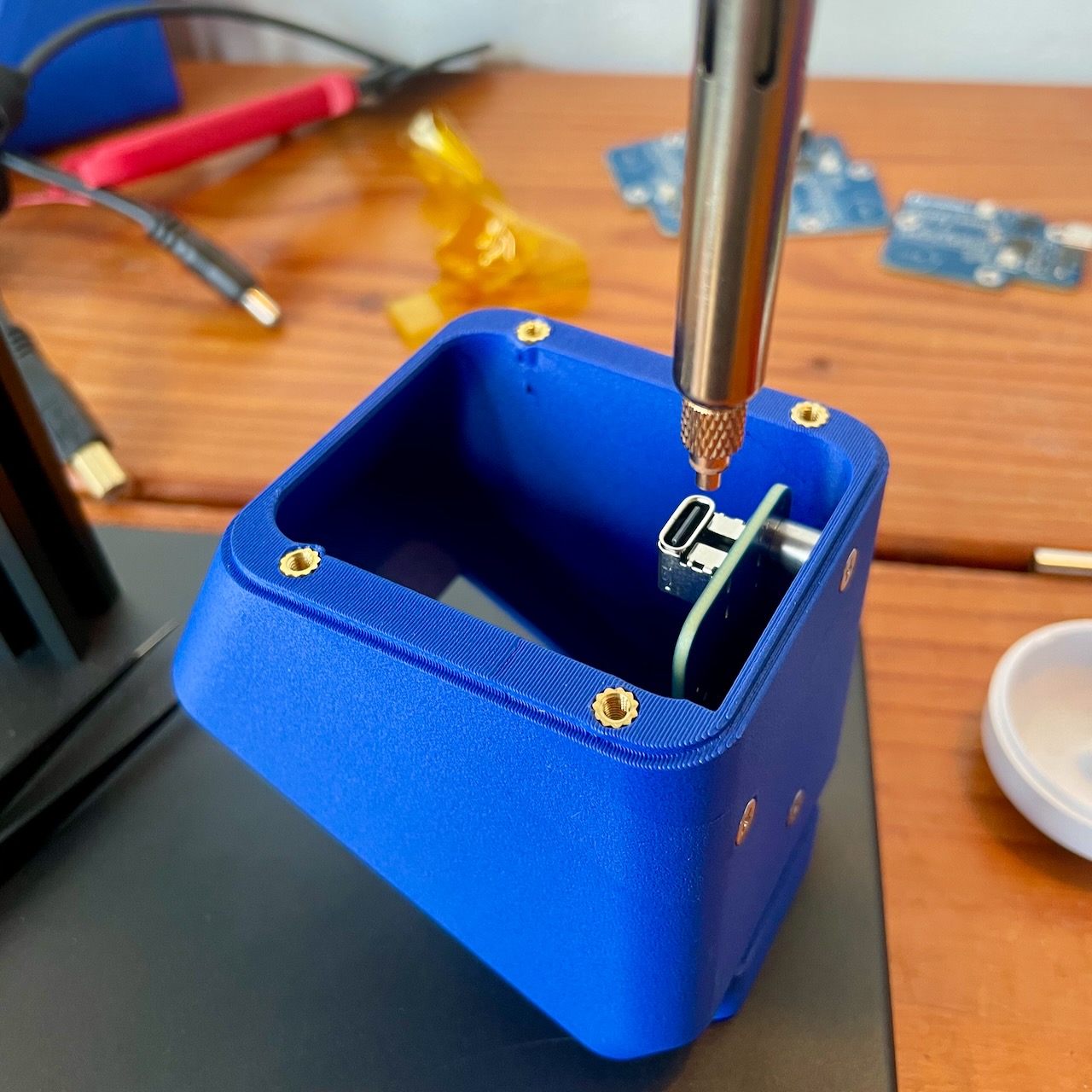

In order to get everything set up the cart is connected via USB to the companion app which sends over the network info, from there the Pico stores it in flash for use later. There are still plenty of improvements to be made so the whole process is easier, mostly notably mDNS.

The Result

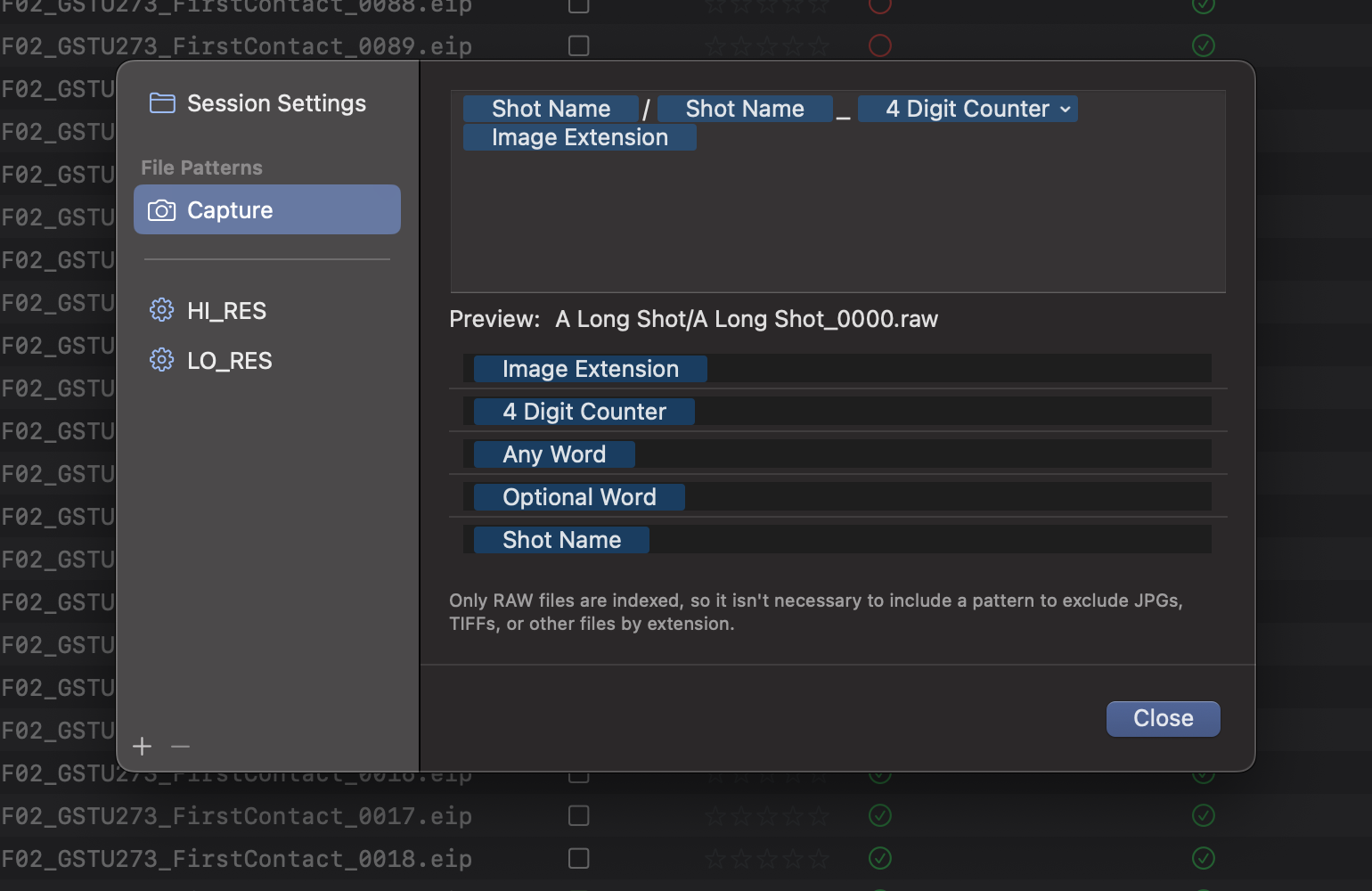

It took weeks of tinkering with the software and hardware, and so much rewiring, but it did all eventually work. The Pico can write the binary to the EEPROM, which the GameBoy launches, and finally sends commands via RAM back to the Pico which forwards them wirelessly to the client software that controls Capture One.

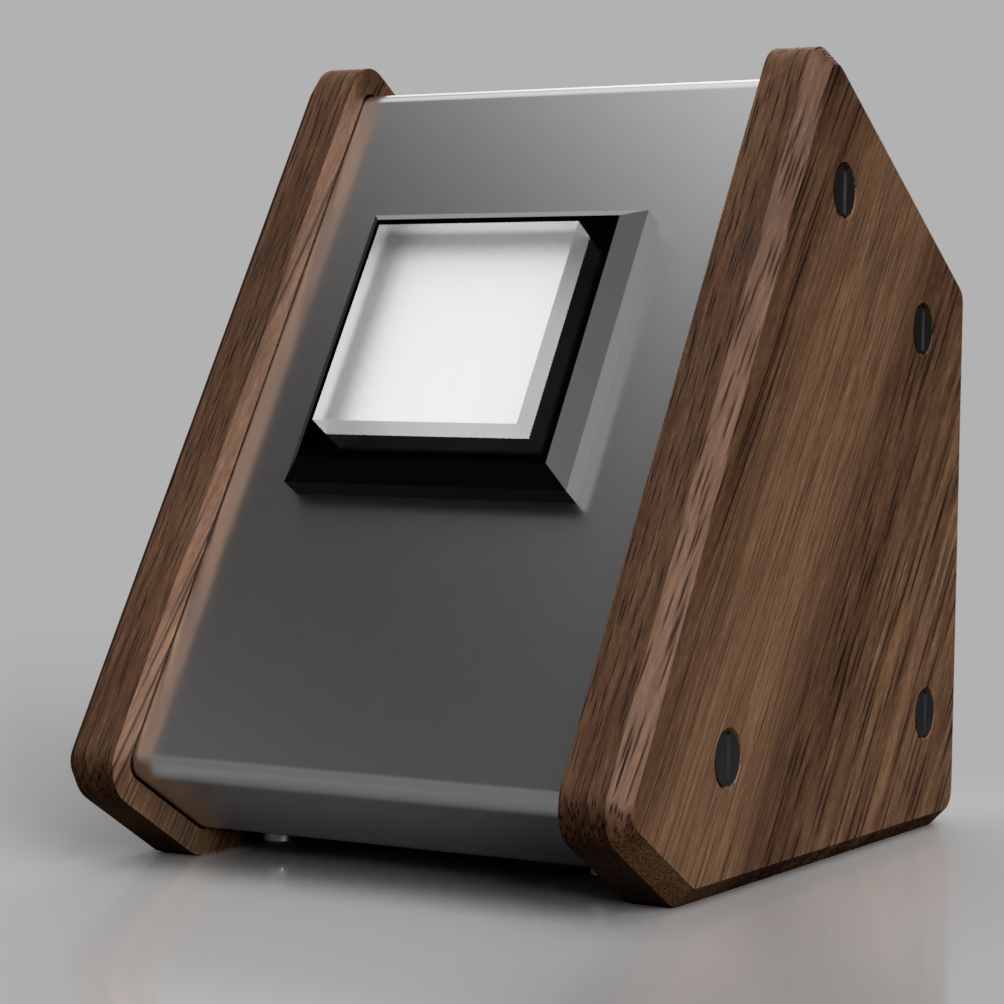

However that's just a tangle of wires on a breadboard, the next step is putting it all together on a PCB. That's going to be a separate post in the future, with its own tales of design and debugging, of which there are many.